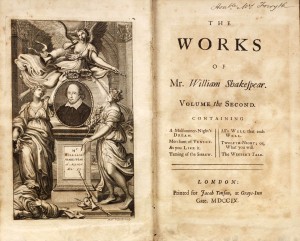

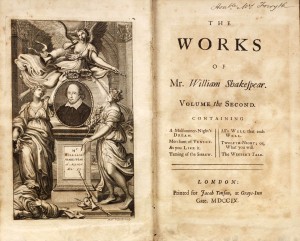

The edition of Shakespeare by Joseph Rann. This is an undistinguished publication from a scholarly point of view, but attractively printed. Joseph Rann (1733-1811), who was from Birmingham, was educated at Trinity College Oxford, and became vicar of Holy Trinity Coventry, a benefice he held for almost forty years.

The edition of Shakespeare by Joseph Rann. This is an undistinguished publication from a scholarly point of view, but attractively printed. Joseph Rann (1733-1811), who was from Birmingham, was educated at Trinity College Oxford, and became vicar of Holy Trinity Coventry, a benefice he held for almost forty years.

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (11): Joseph Rann edition (1786-91)

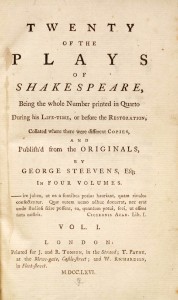

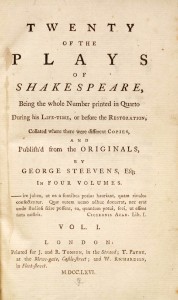

George Steevens (1736-1800) was born of wealthy parents, attended Eton and King’s College (Cambridge), and set about a career as an independent scholar, specializing mainly in Shakespeare.

George Steevens (1736-1800) was born of wealthy parents, attended Eton and King’s College (Cambridge), and set about a career as an independent scholar, specializing mainly in Shakespeare.

The edition shown here is a selection of “the whole number printed in quarto during his lifetime, or before the restoration,” the texts of which Steevens apparently obtained from David Garrick.

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (10): the Steevens “20 plays” edition of 1766

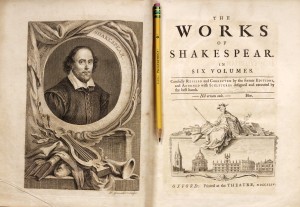

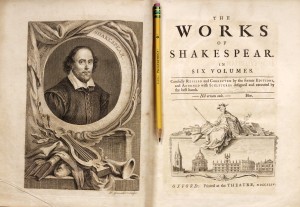

Sir Thomas Hanmer (1677-1746) was Speaker of the House of Commons from 1714-15, thought of himself as a serious editor, who probably had the idea of editing Shakespeare after Theobald’s edition came out (Hanmer’s annotated copy of Theobald is in the Folger Shakespeare Library).

Sir Thomas Hanmer (1677-1746) was Speaker of the House of Commons from 1714-15, thought of himself as a serious editor, who probably had the idea of editing Shakespeare after Theobald’s edition came out (Hanmer’s annotated copy of Theobald is in the Folger Shakespeare Library).

Generally disregarded as an editorial effort, it is also hailed as a beautifully produced and illustrated book, and was a commercial success.

Shown here is a later edition (1751) in smaller format–the same pencil is scanned with both to show relative size.

Shown here is a later edition (1751) in smaller format–the same pencil is scanned with both to show relative size.

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (9): the Hanmer edition of 1743-44

Lewis Theobald (1688-1744), a lawyer who enjoyed a limited success in the commercial theater, published a 194-page attack on Pope’s edition of Shakespeare in 1726.

Lewis Theobald (1688-1744), a lawyer who enjoyed a limited success in the commercial theater, published a 194-page attack on Pope’s edition of Shakespeare in 1726.

Like Pope, Theobald set out his editorial program in the Preface to his edition of Shakespeare, first published in 1733.

“Rowe had presented his readers with a clean page, containing his version of Shakespeare’s plays, formatted according to the conventions of the early eighteenth century and–in common with the seventeenth-century folios–lacking in annotation. Pope’s text was elegantly printed on the wider expanse of a quarto page, with generous margins . . . Theobald made a break with this general convention. In his edition, annotation became both more frequent and more intrusive on the page.”

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (8): Theobald’s 2nd edition of 1740

Unfortunately our copy of the Rowe edition is incomplete, and has been damaged by water.

Unfortunately our copy of the Rowe edition is incomplete, and has been damaged by water.

Nicholas Rowe (1674-1718) was a lawyer, playwright, and minor politician. In his editing of Shakespeare, Rowe essentially followed the Fourth Folio edition of 1685, although he claimed to have arrived at the text by comparing “the several editions.” He did, however, restore some passages in Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, Henry V, and King Lear from early texts.

In addition to being the first illustrated edition of Shakespeare’s collected works, this set marks the first octavo edition, the first to contain a biography of Shakespeare, and the first edition to bear an editor’s name. The seventh volume, produced by Edward Curll, contains poems. Rowe worked mainly from Fourth Folio. His contributions included lists of dramatis personae, act and scene divisions, and characters’ entrances and exits. His “Some Account of the Life, &c., of Mr. William Shakespear” served as the standard Shakespeare biography for the eighteenth century.

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (7): Rowe edition (1709)

Finally we come to our facsimile of the Fourth Folio, which was originally issued in 1685, when ownership of the plays had again changed hands:

Finally we come to our facsimile of the Fourth Folio, which was originally issued in 1685, when ownership of the plays had again changed hands:

“Eleanor Cotes’ rights passed to John Martin and Henry Herringman in August of 1674. Martin died in 1674 and his widow, Sarah, assigned his rights to Robert Scott (about whom little is known) in 1683. While Eleanor Cotes is known to have owned half the rights to the texts originally registered by Jaggard and Blount, it seems that Martin and Herringman believed that they had acquired these plays outright . . . In any event, by 1685 Henry Herringman was clearly the dominant rights-holder and his name appears as publisher on all of the title-pages of the Fourth Folio” [there are at least three states of the t.p.] . . .

“The Fourth Folio differs from the Second and Third in that it is not a page-for-page reprint of the 1623 original. The volume falls into three divisions, each with separate signatures and pagination: the Comedies; the Histories plus the Tragedies up to and including Romeo and Juliet; and the remainder of the Tragedies, together with the apocryphal plays added in 1664. The three sections are clearly the work of three distinct printshops.”

From Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (6): The Fourth Folio

We have an excellent facsimile of the Third Folio, which appeared in 1663, and a second issue in 1664, augmented, as the title-page tells us, with seven plays: Pericles; The London Prodigall; The History of Thomas Lord Cromwell; Sir John Oldcastle Lord Cobham; The Puritan Widow; A York-Shire Tragedy; The Tragedy of Locrine. Only Pericles is considered to be Shakespeare’s (partially)

Because of their scarcity relative to the other folios, it is though that many were destroyed before distribution in the London fire of 1666.

According to one of the standard scholarly works on the subject, the Third Folio “does more credit to the printing house which turned it out and is largely free from gross typographical errors. But from the fact that it unintentionally omitted a great many words, we infer that the proof reading given it was not sufficiently careful to catch unobtrusive compositor’s errors. The editor, furthermore, was not nearly so aggressive as the editor of F2 [2nd Folio] and did not feel free to go further than to correct blunders that make nonsense of meaning, grammatical improprieties, an archaic diction.”

–Black & Shaaber, Shakespeare’s Seventeenth-Century Editors, 1632-1685 (1937), who identify 943 editorial changes made in the Third Folio.

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (5): The Third Folio

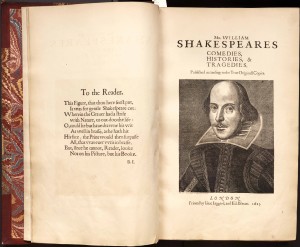

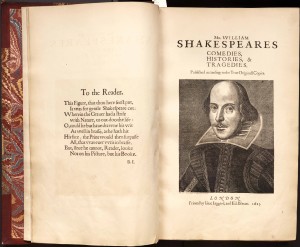

Unfortunately we do NOT have the so-called “First Folio” (London, 1623) of Shakespeare–a critically important book in Shakespeare studies as the first collected edition of his plays, wherein were printed for the first time eighteen plays! They were as follows:

Unfortunately we do NOT have the so-called “First Folio” (London, 1623) of Shakespeare–a critically important book in Shakespeare studies as the first collected edition of his plays, wherein were printed for the first time eighteen plays! They were as follows:

The Tempest, Two Gentlemen of Verona, Measure for Measure, The Comedy of Errors, As You Like It, The Taming of the Shrew, All’s Well that Ends Well, Twelfth Night, The Winter’s Tale, King John, Henry VI part I, Henry VIII, Coriolanus, Timon of Athens, Julius Caesar, Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, and Cymbeline.

We do, however, have an excellent facsimile of it, produced in 1866 by Howard Staunton, which was created using the newly invented technology of photo-lithography. These were initially issued in sixteen (16) monthly parts at 10s. 6d. per part, or a total of 8 guineas–the price was relatively high (about $1,500 in today’s money).

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (4): The First Folio

In 2012, through the generosity of the Watkinson Board of Trustees, we were able to acquire a copy of the “2nd Folio” (1632) of Shakespeare. This copy had been in one family’s possession since the mid-19th-century.

This second edition, as it were, was issued with five different title-pages (representing the five different principal investors). However, since ours lacked the title-page, we don’t know which issue we have. The 2nd Folio bears over 1,200 corrections (mostly in restoring meter and the spelling of Latin phrases and classical names), but is principally famous for the dedicatory poem to Shakespeare written in 1630 by John Milton—which was his very first publication of English verse (he was 24).

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (3): The Second Folio

As noted, our copy of the fourth edition (technically) of Othello is only one of two 17th-century “player’s quarto” editions of Shakespeare in the Watkinson.

“We should remember that no concept of ‘copyright,’ in its modern sense, existed in Shakespeare’s time. ‘Ownership’ of texts was confined to publishers, who established their right to produce a work by licensing it with their professional body, the Stationers’ Company; a publisher might additionally guarantee ownership of the text by paying a futher fee to have the title entered into the Stationers’ Register. An author who brought a new work to a publisher would be paid for the text—sometimes, in part at least, by being given copies of the printed book—but this payment secured outright ownership of the text . . . In the case of theatrical scripts, a further transactional layer intervened between the writer and the publisher. Plays for commercial production were, for the most part, commissioned by theatre companies from a pool of jobbing playwrights, many of them working collaboratively to produce scripts . . . Once purchased, the play became the property of the theatre company.”

–Murphy, Shakespeare in Print

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (2): Othello quarto

George Steevens (1736-1800) was born of wealthy parents, attended Eton and King’s College (Cambridge), and set about a career as an independent scholar, specializing mainly in Shakespeare.

George Steevens (1736-1800) was born of wealthy parents, attended Eton and King’s College (Cambridge), and set about a career as an independent scholar, specializing mainly in Shakespeare.