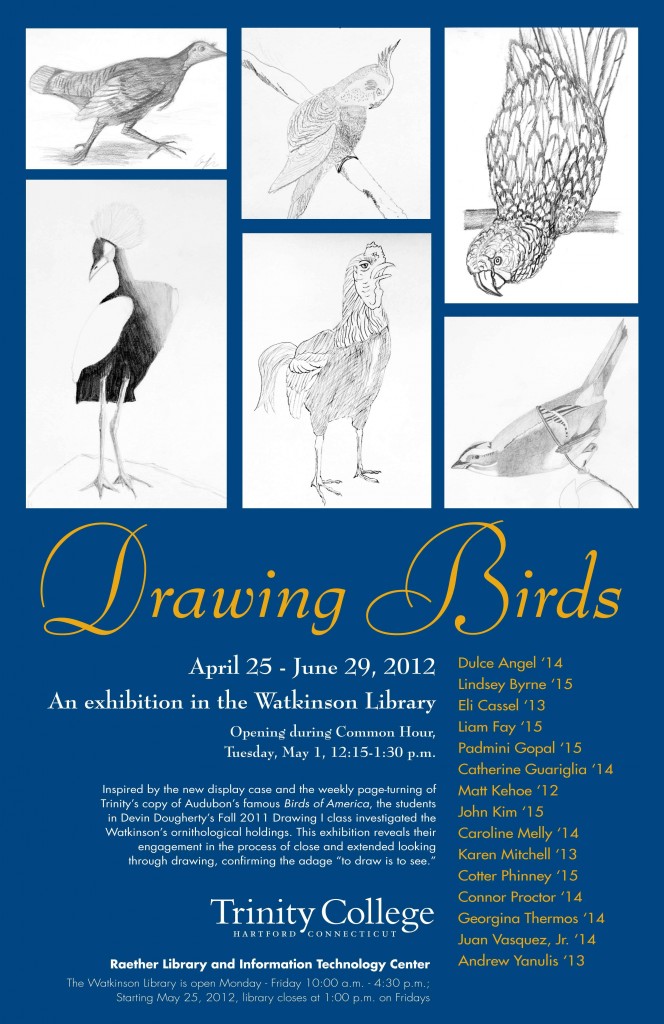

Last semester the students in Devin Dougherty’s “Drawing I” class came into the Watkinson for two three-hour sessions to sketch birds. These were not (of course) LIVE birds, but images that can be found in our amazing collection of ornithological books. During the Common Hour (12-1:30) on Tuesday May 1st, we will have an opening reception for this exhibit, with prof. Dougherty and some of the student artists present. Please stop by!

On Thursday May 3rd, at 5:30pm in the Watkinson Library reading room, our five Creative Fellows will present their projects (amid light refreshments) to the Trinity community. Faculty and students who wish to see some of the possibilities of this program “made real” are especially invited. One project, still in process, is Chloe Miller’s (’14) online semi-fictional travelogue across the temporal and geographical spectrum, based on sources she found here.

On Thursday May 3rd, at 5:30pm in the Watkinson Library reading room, our five Creative Fellows will present their projects (amid light refreshments) to the Trinity community. Faculty and students who wish to see some of the possibilities of this program “made real” are especially invited. One project, still in process, is Chloe Miller’s (’14) online semi-fictional travelogue across the temporal and geographical spectrum, based on sources she found here.

You will also hear music composed by Francis Russo (’13), view Norse myths retold by John Bower (’12), hear poetry composed, hand-printed and read by Lelsie Ahlstrand (’12), and see a film produced by Perin Adams (’13). ALL of these projects were based on books and manuscripts found in the Watkinson:

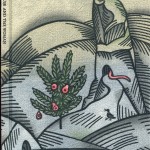

“I regret that I am unable to give any account of the habits of a species which I have honoured with the name of a naturalist whose merits are so well known to the learned world. The individual represented in the plate I shot upwards of twenty years ago, and have never met with another of its kind. It was in the month of May, on a small island of the Perkioming [i.e. Perkiomen] Creek, forming part of my farm of Mill Grove, in the State of Pennsylvania. The bird was fluttering amongst grasses, uttering an often repeated cheep.

“I regret that I am unable to give any account of the habits of a species which I have honoured with the name of a naturalist whose merits are so well known to the learned world. The individual represented in the plate I shot upwards of twenty years ago, and have never met with another of its kind. It was in the month of May, on a small island of the Perkioming [i.e. Perkiomen] Creek, forming part of my farm of Mill Grove, in the State of Pennsylvania. The bird was fluttering amongst grasses, uttering an often repeated cheep.

The plant on which it is represented is that on which it was perched when I shot it, and is usually called Spider-wort. It grows in damp and shady places, as well as sometimes in barren lands, near the banks of brooks.

–J. J. Audubon, Ornithological Biography, I (1831), 153 [excerpted].

“The flight of the Towhe Bunting is short, low, and performed from one bush or spot to another, in a hurried manner, with repeated strong jerks of the tail, and such quick motions of the wings, that one may hear their sound, although the bird should happen to be out of sight . . . it is a diligent bird, spending its days in searching for food and gravel, amongst the dried leaves and in the earth, scratching with great assiduity, and every now and then uttering the notes tow-hee, from which it has obtained its name . . .

“The flight of the Towhe Bunting is short, low, and performed from one bush or spot to another, in a hurried manner, with repeated strong jerks of the tail, and such quick motions of the wings, that one may hear their sound, although the bird should happen to be out of sight . . . it is a diligent bird, spending its days in searching for food and gravel, amongst the dried leaves and in the earth, scratching with great assiduity, and every now and then uttering the notes tow-hee, from which it has obtained its name . . .

The favorite haunts of the Towhe Buntings are dry, barren tracts, but not, as others have said, low and swampy grounds, at least during the season of incubation. In the Barrens of Kentucky they are found in the greatest abundance . . .

They generally rest on the ground at night, when many are caught by weasles and other small quadrupeds. None of them breed in Louisiana, not indeed in the state of Mississippi, until they reach the open woods of the Choctaw Indian Nation.”

–J. J. Audubon, Ornithological Biography, I (1831), 150-151 [excerpted].

“This, reader, is one of the scarce birds that visit the United States from the south, and I have much pleasure in being able to give you an account of it, as hitherto little or nothing has been known of its history.

“This, reader, is one of the scarce birds that visit the United States from the south, and I have much pleasure in being able to give you an account of it, as hitherto little or nothing has been known of its history.

It is an inhabitant of Louisiana during the spring and summer months, when it resorts to the thick cane-breaks of the alluvial lands near the Mississippi, and the borders of the numberless swamps that lie in a direction parallel to that river . . . In the month of May 1809, I killed a male and a female of this species, near the mouth of the Ohio, while on a shooting expedition after young swans. The following spring, I killed a female near Henderson in Kentucky. In 1821, I again procured a pair, with their nest and eggs, near the mouth of the Bayou La Fourche, on the Mississippi, and since that period have killed eight or ten pairs . . .

The manners of this bird are not those of the Titmouse, Fly-catcher, or Warbler, but partake of those of all three. It has the want of shyness exhibited in the Red-eyed and Yellow-throated Fly-catchers. It hangs to bunches of small berries, feeding upon them as a Titmouse does on buds of trees; and again searches among the leaves and along the twigs of low bushes, like most of the Warblers. On the other hand, it differs from all these in their principal habits. Thus, it never snaps at insects on the wing, although it pursues them; it never attacks small birds and kills them by breaking in their skulls, as the Titmouse does; nor does it hold its prey under its foot in the way of the Yellow-throated Fly-catcher or Vireo, a habit which allies the latter to the Shrikes . . . I have never heard it utter a note beyond that of a querulous low murmuring sound, when chasing another bird from the vicinity of its nest.”

–J. J. Audubon, Ornithological Biography, I (1831), 147-148 [excerpted].

We’ve just acquired a group of books by and about Lafcadio Hearn, which will join an already impressive collection both in the Watkinson and the main library stacks.

Lafcadio Hearn was a mongrel child of the world,—a global villager,—a man unattached to country, kin, or creed. He was a sensitive underdog marginalized for his proclivities from beginning to end. Born Patrick Lafcadio Hearn on June 27, 1850, on the Ionian island of Leucadia just north of Ithaca (of Homeric fame), Lafcadio’s own odyssey would bring him to far shores and settings, both exotic and mundane.

In 2009 the Library of America published a selection of Hearn’s works, edited by Christopher Benfey, entitled Lafcadio Hearn: American Writings. In an interview Benfey stated, “I’m completely convinced that Hearn’s time has come. He famously wrote that he worshiped ‘the Odd, the Queer, the Strange, the Exotic, the Monstrous.’ Such pronouncements have made it easy to dismiss him as some oddball combination of Poe and Gauguin, living in an escapist world of dreams. But what Hearn was really interested in was the astonishing variety of human life.”

Hearn’s mother, Rosa Antonia Cassimati, was from Cerigo (known to the Greeks as Cythera); his father, Charles Bush Hearn, was an Irish surgeon and officer in the British Army. Their romance was not favored by either of their families. After Charles was re-assigned to the West Indies, he managed to send Rosa and young Patrick to Dublin, where his relations greeted these “gypsy” additions to their household with predictable warmth. An estranged aunt who doted on Patrick took them in, but after Charles finally returned to Ireland and established a little household in 1853 it became clear he had lost interest in Rosa. He took a new military assignment in the West Indies, and by the time he returned in 1856, Rosa had gone back to Greece and left five-year-old Patrick alone with his great-aunt. Charles Hearn annulled their marriage, and the Hearn family hid the boy from his mother when she returned to Ireland to see him.

At age nine or ten young Patrick discovered the library in his great-aunt’s house, and found several books of art containing images from Greek mythology. “How my heart leaped and fluttered on that happy day!” he would later write. “Breathless I gazed; and the longer that I gazed the more unspeakably lovely those faces and forms appeared. Figure after figure dazzled, astounded, bewitched me.” This fascination with the elder gods did not sit well with his aunt, a devout Catholic, who sent him to a boarding school—three quarters monastery and one quarter military academy—run by “a hateful venomous-hearted old maid.” Guy de Maupassant, who attended the school months after Lafcadio left, wrote “I can never think of the place even now without a shudder. It smelled of prayers the way a fish market smells of fish . . . We lived there in a narrow, contemplative, unnatural piety—and also in a truly meritorious state of filth . . . As for baths, they were as unknown as the name of Victor Hugo. Our masters apparently held them in the greatest contempt.”

When he was sixteen Hearn suffered an accident which blinded his left eye, and from then on he would instinctively cover it with his left hand in conversation, or look down or to the left when photographed. Financial troubles forced him to seek schooling in London while living with a dock worker and his wife (distant relatives)—and there he made his first forays into the underside of urban existence, fascinated and repelled by “the wolf’s side of life, the ravening side, the apish side; the ugly facets of the monkey puzzle.” Fed up with his dilatory and dreamy ways, his family gave him a one-way ticket to New York City and told him to make his way to Cincinnati, to another set of relatives who didn’t want the strange young man. Penniless and homeless, he wandered the streets of the river town until he found work doing odd jobs at one of the local newspapers. In October of 1872 he submitted a review of Tennyson’s Idylls of the King to the editor of the Cincinnati Enquirer, which became his first signed publication. Thus was born a literary journalist—an intelligent, provocative observer with a ripe facility for language and a penchant for exposing the horror and the humor of everyday urban life.

Christopher Benfey notes, “One of our best current travel writers, Pico Iyer, uses the phrase ‘global soul’ for people who have adapted themselves to our new world of mass migration and globalization. Hearn, it seems ot me, was an early version of a global soul. Born into the British Empire, he experienced firsthand the bitter divisions of the American Gilded Age, and lived to witness the rise of a new power in Asia: Imperial Japan.”

“Late in his life,” Benfy continues, “Hearn became the Brothers Grimm for Japan, assembling the bare bones of some Japanese ghost stories and transmuting them—with a whiff of Poe and Mérimée—into literary masterpieces.”

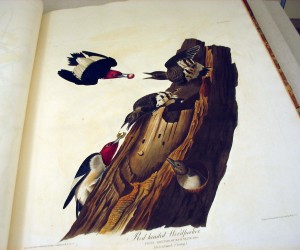

“You have now, kind reader, under consideration a family of woodpeckers, the general habits of which are so well known in our United States, that, were I assured of your having traversed the woods of America, I should feel disposed to say little about them.

“You have now, kind reader, under consideration a family of woodpeckers, the general habits of which are so well known in our United States, that, were I assured of your having traversed the woods of America, I should feel disposed to say little about them.

The Red-heads . . . remain in the southern districts [of the U.S.] during the whole winter, and breed there in summer. The greater number, however, pass to countries farther south. Their migration takes place under night, is commenced in the middle of September, and continues for a month or six weeks. They then fly very high above the trees, far apart, like a disbanded army, propelling themselves by reiterated flaps of the wings . . .”

I would not recommend to anyone to trust their fruit to the Red-heads; for they not only feed on all kinds as they ripen, but destroy an immense quantity besides. No sooner are the cherries seen to redden, than these birds attack them. They arrive on all sides, coming from a distance of miles . . . Trees of this kind are stripped clean by them . . .

It is impossible to form any estimate of the number of these birds seen in the United States during the Summer months; but this much I may safely assert, that an hundred have been shot upon a single cherry tree in one day.”

–J. J. Audubon, Ornithological Biography, I (1831), 141-142 [excerpts].

Book history!

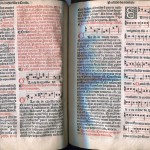

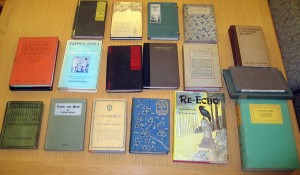

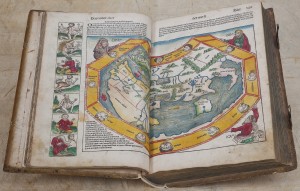

Jonathan Elukin speaks to his Guided Studies class about the transition of scroll to codex and manuscript to print in late medieval and early modern Europe using sources in the Watkinson. Among the books on the table:

One of our copies of Liber Chronicarum (the “Nuremberg Chronicle”), published in 1493, which offers nothing less than a representative picture of geographical and historical knowledge on the eve of Columbus’s voyages and the expansion of Europe into the western hemisphere.

One of our copies of Liber Chronicarum (the “Nuremberg Chronicle”), published in 1493, which offers nothing less than a representative picture of geographical and historical knowledge on the eve of Columbus’s voyages and the expansion of Europe into the western hemisphere.

Many of the illustrations, such as the two-page view of Jerusalem, were based on the most recent reports of travelers (usually merchants).

For those students and faculty who wish to read this book and do not know Latin, we have just acquired the first two volumes of an excellent new translation, which will make this landmark book accessible to all undergraduates.

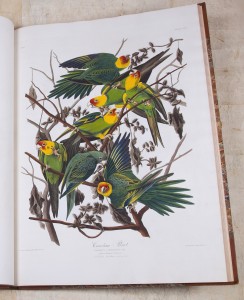

If you only visit the Watkinson once this semester, let it be this week! One of the most famous birds in the Audubon (both because of the artistry and because it is now extinct) is on display until Friday.

If you only visit the Watkinson once this semester, let it be this week! One of the most famous birds in the Audubon (both because of the artistry and because it is now extinct) is on display until Friday.

“Doubtless, kind reader, you will say, while looking at the seven figures of Parakeets represented in the plate, that I spared not my labour. I never do, so anxious am I to promote your pleasure . . .

The Parrot does not satisfy himself with cockle-burs, but eats or destroys almost every kind of fruit indiscriminately, and on this account is always an unwelcome visitor to the planter, the farmer, or the gardener. The stacks of grain put up in the field are resorted to by flocks of these birds, which frequently cover them so entirely, that they present to the eye the same effect as if a brilliantly coloured carpet had been thrown over them. They cling around the whole stack, pull out the straws, and destroy twice as much of the grain as would suffice to satisfy their hunger. They assail the pear and apple-trees, when the fruit is yet very small and far from being ripe, and this merely for the sake of the seeds. As on the stalks of corn, they alight on the apple-trees of our orchards, or the pear-trees in the gardens, in great numbers; and, as if through mere mischief, pluck off the fruits, open them up to the core, and, disappointed at the sight of the seeds, which are yet soft and of a milky consistence, drop the apple or pear, and pluck another, passing from branch to branch, until the trees which were before so promising, are left completely stripped, like the ship water-logged and abandoned by its crew, floating on the yet agitated waves, after the tempest has ceased. They visit the mulberries, pecan-nuts, grapes, and even the seeds of the dog-wood, before they are ripe, and on all commit similar depredations. The maize alone never attracts their notice.

Do not imagine, reader, that all these outrages are borne without severe retaliation on the part of the planters. So far from this, the Parakeets are destroyed in great numbers, for whilst busily engaged in plucking off the fruits or tearing the grain from the stacks, the husbandman approaches them with perfect ease, and commits great slaughter among them. All the survivors rise, shriek, fly round about for a few minutes, and again alight on the very place of most imminent danger. The gun is kept at work; eight or ten, or even twenty, are killed at every discharge. The living birds, as if conscious of the death of their companions, sweep over their bodies, screaming as loud as ever, but still return to the stack to be shot at, until so few remain alive, that the farmer does not consider it worth his while to spend more of his ammunition. I have seen several hundreds destroyed in this manner in the course of a few hours, and have procured a basketful of these birds at a few shots, in order to make choice of good specimens for drawing the figures by which this species is represented in the plate now under your consideration.”

–J. J. Audubon, Ornithological Biography, I (1831), 135-136 [excerpts].

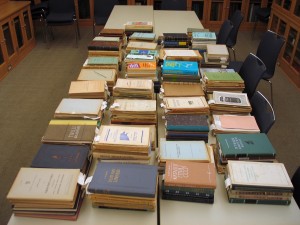

We have just unpacked eight (8) cartons of just over 300 books on Russian ornithology which we purchased from a well-respected Dutch antiquarian book dealer. These books were originally part of a much larger collection put together by the great bibliophile Henry Bradley Martin (1906-1988), whose collections of ornithology, 16th- and 17th-century English literature, and 19th-century American and French literature were sold through Sotheby’s (New York) in several well-publicized sales in 1989.

We have just unpacked eight (8) cartons of just over 300 books on Russian ornithology which we purchased from a well-respected Dutch antiquarian book dealer. These books were originally part of a much larger collection put together by the great bibliophile Henry Bradley Martin (1906-1988), whose collections of ornithology, 16th- and 17th-century English literature, and 19th-century American and French literature were sold through Sotheby’s (New York) in several well-publicized sales in 1989.

The books and pamphlets you see here constituted about half of Lot 1845 of Sale 5953 (Session II, December 13, 1989), which was purchased by another Dutch dealer.

In terms of research, this acquisition is a leap forward in the (admittedly obscure) field of Russian ornithology. A very quick check against our two closest rivals in terms of historic ornithological collections (Yale and Cornell), has yielded the following analysis:

Of 300 titles, Trinity has 17, Yale has 18, and Cornell has 17. There is considerable overlap–of the titles owned by the three libraries, 7 are only at Trinity, 3 are at both Trinity & Yale, 4 are only at Yale, 6 are at both Yale and Cornell, 6 are only at Cornell, and 5 are at all three places. With this acquisition, over 280 titles can only be found here at Trinity.