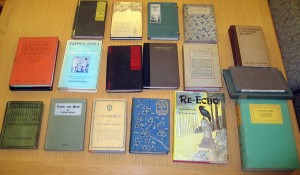

We’ve just acquired a group of books by and about Lafcadio Hearn, which will join an already impressive collection both in the Watkinson and the main library stacks.

Lafcadio Hearn was a mongrel child of the world,—a global villager,—a man unattached to country, kin, or creed. He was a sensitive underdog marginalized for his proclivities from beginning to end. Born Patrick Lafcadio Hearn on June 27, 1850, on the Ionian island of Leucadia just north of Ithaca (of Homeric fame), Lafcadio’s own odyssey would bring him to far shores and settings, both exotic and mundane.

In 2009 the Library of America published a selection of Hearn’s works, edited by Christopher Benfey, entitled Lafcadio Hearn: American Writings. In an interview Benfey stated, “I’m completely convinced that Hearn’s time has come. He famously wrote that he worshiped ‘the Odd, the Queer, the Strange, the Exotic, the Monstrous.’ Such pronouncements have made it easy to dismiss him as some oddball combination of Poe and Gauguin, living in an escapist world of dreams. But what Hearn was really interested in was the astonishing variety of human life.”

Hearn’s mother, Rosa Antonia Cassimati, was from Cerigo (known to the Greeks as Cythera); his father, Charles Bush Hearn, was an Irish surgeon and officer in the British Army. Their romance was not favored by either of their families. After Charles was re-assigned to the West Indies, he managed to send Rosa and young Patrick to Dublin, where his relations greeted these “gypsy” additions to their household with predictable warmth. An estranged aunt who doted on Patrick took them in, but after Charles finally returned to Ireland and established a little household in 1853 it became clear he had lost interest in Rosa. He took a new military assignment in the West Indies, and by the time he returned in 1856, Rosa had gone back to Greece and left five-year-old Patrick alone with his great-aunt. Charles Hearn annulled their marriage, and the Hearn family hid the boy from his mother when she returned to Ireland to see him.

At age nine or ten young Patrick discovered the library in his great-aunt’s house, and found several books of art containing images from Greek mythology. “How my heart leaped and fluttered on that happy day!” he would later write. “Breathless I gazed; and the longer that I gazed the more unspeakably lovely those faces and forms appeared. Figure after figure dazzled, astounded, bewitched me.” This fascination with the elder gods did not sit well with his aunt, a devout Catholic, who sent him to a boarding school—three quarters monastery and one quarter military academy—run by “a hateful venomous-hearted old maid.” Guy de Maupassant, who attended the school months after Lafcadio left, wrote “I can never think of the place even now without a shudder. It smelled of prayers the way a fish market smells of fish . . . We lived there in a narrow, contemplative, unnatural piety—and also in a truly meritorious state of filth . . . As for baths, they were as unknown as the name of Victor Hugo. Our masters apparently held them in the greatest contempt.”

When he was sixteen Hearn suffered an accident which blinded his left eye, and from then on he would instinctively cover it with his left hand in conversation, or look down or to the left when photographed. Financial troubles forced him to seek schooling in London while living with a dock worker and his wife (distant relatives)—and there he made his first forays into the underside of urban existence, fascinated and repelled by “the wolf’s side of life, the ravening side, the apish side; the ugly facets of the monkey puzzle.” Fed up with his dilatory and dreamy ways, his family gave him a one-way ticket to New York City and told him to make his way to Cincinnati, to another set of relatives who didn’t want the strange young man. Penniless and homeless, he wandered the streets of the river town until he found work doing odd jobs at one of the local newspapers. In October of 1872 he submitted a review of Tennyson’s Idylls of the King to the editor of the Cincinnati Enquirer, which became his first signed publication. Thus was born a literary journalist—an intelligent, provocative observer with a ripe facility for language and a penchant for exposing the horror and the humor of everyday urban life.

Christopher Benfey notes, “One of our best current travel writers, Pico Iyer, uses the phrase ‘global soul’ for people who have adapted themselves to our new world of mass migration and globalization. Hearn, it seems ot me, was an early version of a global soul. Born into the British Empire, he experienced firsthand the bitter divisions of the American Gilded Age, and lived to witness the rise of a new power in Asia: Imperial Japan.”

“Late in his life,” Benfy continues, “Hearn became the Brothers Grimm for Japan, assembling the bare bones of some Japanese ghost stories and transmuting them—with a whiff of Poe and Mérimée—into literary masterpieces.”

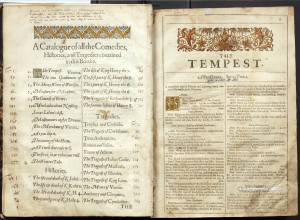

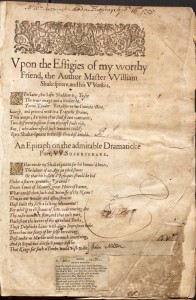

Thanks mostly to the enthusiastic comments made by President Jones during Commencement weekend, we had over 100 visitors to the Watkinson on Saturday to see the recently acquired “Second Folio” of Shakespeare. We don’t often see people literally lining up to see our books, but it is entirely gratifying.

Thanks mostly to the enthusiastic comments made by President Jones during Commencement weekend, we had over 100 visitors to the Watkinson on Saturday to see the recently acquired “Second Folio” of Shakespeare. We don’t often see people literally lining up to see our books, but it is entirely gratifying. Other items which I brought out for the day included two engravings on copper sheets which were used to illustrate Prideaux John Selby’s Illustrations of British Ornithology (published 1834-39), which were placed alongside the book itself. Selby was a contemporary of Audubon, and the two ornithologists compared notes and shared insights when the latter was at work in England.

Other items which I brought out for the day included two engravings on copper sheets which were used to illustrate Prideaux John Selby’s Illustrations of British Ornithology (published 1834-39), which were placed alongside the book itself. Selby was a contemporary of Audubon, and the two ornithologists compared notes and shared insights when the latter was at work in England.