CBAA day 3

This morning I attended the publications/editorial committee, where we discussed the new peer-reviewed journal that the CBAA plans to publish (titled Openings: studies in book art). The first issue is planned for November, and we discussed various ways to generate submissions and to attract peer reviewers.

After that I attended a session of three presenters: Michele Burgess (San Diego State U.), Martha Carothers (U. of Delaware), and Kitty Marryat (Scripps College). All of them presented work done by their book arts students, and even though their courses and programs vary in many ways, several issues were brought into focus for me as I plan a small program at Trinity. First and most important: if I wish to encourage and facilitate student work in the book arts, it will require a detailed plan, with specific deadlines and a structure of oversight and advising built into it, as well as a period of brainstorming, to move the project from the head into the hands. This seems obvious, but it must be emphasized at every turn. I simply do not have the time to do what these people do (since my main function is not as a facutly member), but Kitty made the valuable observation that one can customize this work–from a 3-hour project to that of an entire semester. One other necessity is to make sure that all major work is accompanied by a process journal, written by the student.

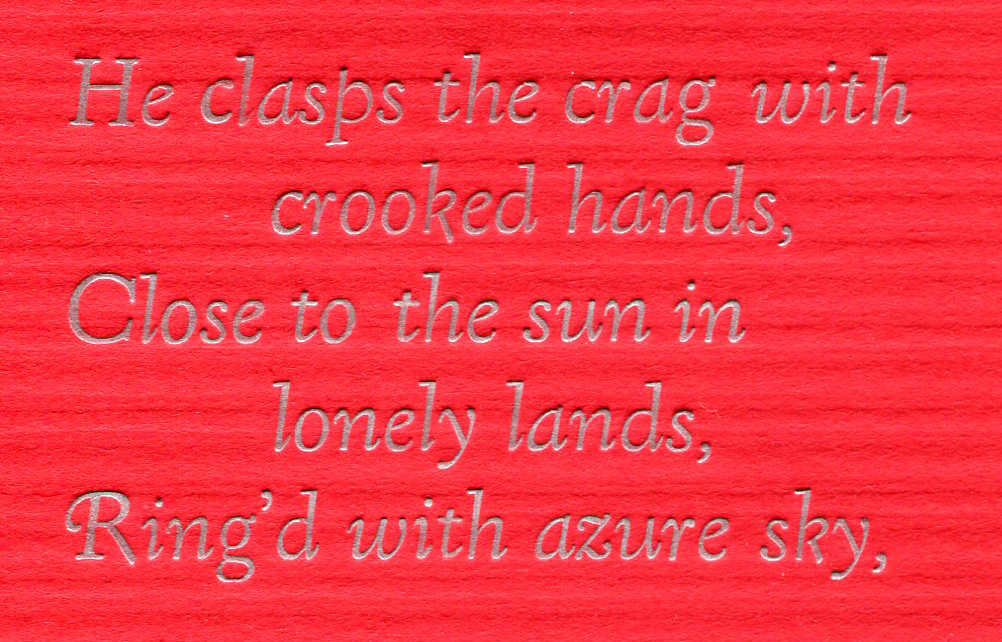

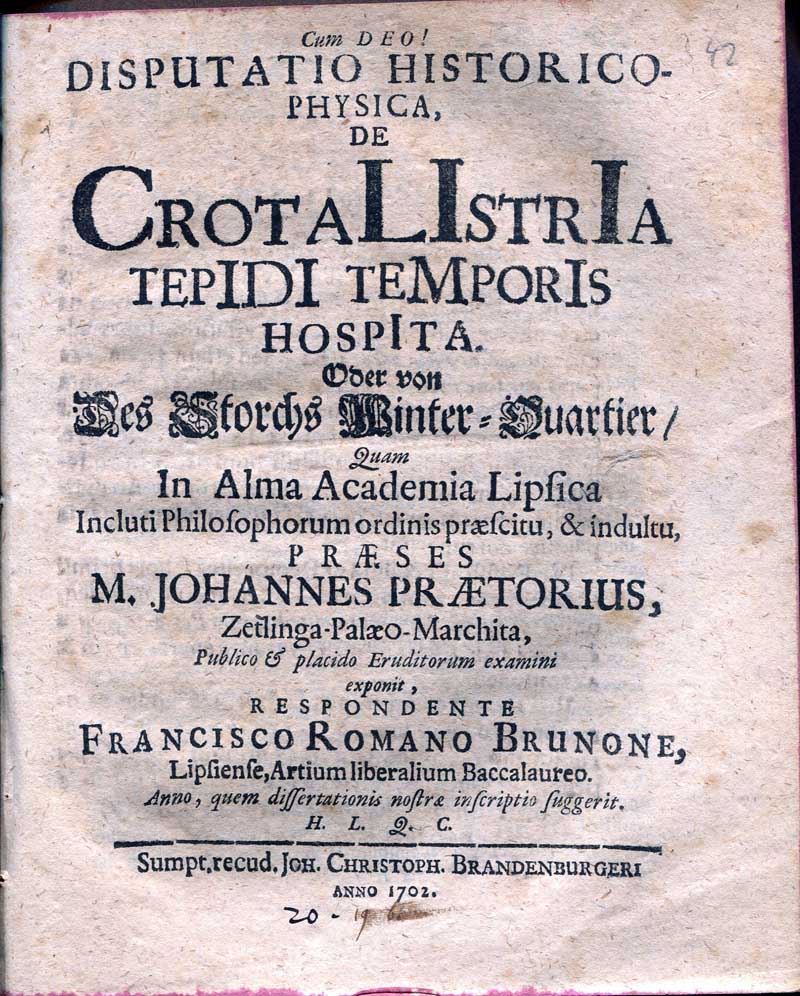

The next session I attended featured Matthew Aron and Shawn Simmons (book artists and designers), Cynthia Thompson (Memphis College of Art), and Laura Capp (a recent recipient of a PhD in English literature from the University of Iowa). Aron and Simmons gave a theoretical talk on “authorship in graphic design and artists’ books,” which was not particularly useful to me. Thompson’s talk focused on keeping the book arts in the curriculum by incorporating traditional type and book design into the larger design arts (this is, of course, more useful to folks who have design programs, like the Hartford Art School). Laura Capp’s presentation, “On my way to becoming a scholar, I cried and learned calligraphy,” was about how her experience in learning calligraphy in many courses taken at the Iowa Center for the Book provided first a creative escape from, and later a valuable perspective on, her dissertation research. Specifically, Capp described how the act of painstakingly writing out some of the poetry she was studying slowed her down enough to perform a much closer reading of the work than she would have done otherwise. I found this a valuable confirmation of what I already believe–which is that once one educates the hands in the act of producing texts, the head understands and appreciates far more deeply the thousands of original works in special collections. More importantly, that deeper understanding can often lead to more grounded and thorough interpretations.

The last session I attended was on “Librarians and Pedagogy,” and featured Laurie Whitehill-Chong (curator at the Rhode Island School of Design), Ruth Rogers (curator at Wellesley College), and Tony White (Director of the Fine Arts Library at IU). All of them spoke about artist’s books being useful in discussing book structure, and I heard for the first time the concept of “hybrid” as applied to books and media. Most interesting to me was Rogers’ acquisition criteria for artist’s books: relevance to the collection, relevance to the curriculum, the extent to which the book documents contemporary issues, the level of craft present in the book, and that it is a book which has in it “more than one reading,” (i.e., does one wan to read it more than once–a subjective but valuable criteria).

I will not go into the other events (tours and receptions) at the conference for obvious reasons, but I came away with a great deal to think about, and many excellent new colleagues.