Pure Nostalgia

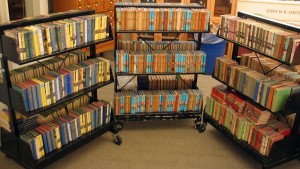

Unpacking 22 boxes of a gift collection this morning has generated pure, unadulterated nostalgia for my earliest passion: reading The Hardy Boys mystery series.

Unpacking 22 boxes of a gift collection this morning has generated pure, unadulterated nostalgia for my earliest passion: reading The Hardy Boys mystery series.

The gift came quite literally from out of the blue. A bookseller in the southwest posted a note to a rare books listserv that his client — a collector in New Mexico — had formed a “study collection” of various juvenile genre series (nearly 700 volumes, including multiple editions of the Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew, the Little Colonel, The Dana Girls, the Bobbsey Twins, Judy Bolton, Connie Blair, and works by Alcott, Montgomery, Porter, and Wiggin), and she wanted to gift it to an institution. Three minutes after this was posted, I responded, and was the first institution to do so–and therefore got the prize!

And what a prize it is. It joins our other children’s books (ca. 2,000 volumes) which also connects to our Barnard collection (ca. 7,000 volumes) on early education, effectively allowing our students to study what American youth read from the 1820s through the 1950s.

And what a prize it is. It joins our other children’s books (ca. 2,000 volumes) which also connects to our Barnard collection (ca. 7,000 volumes) on early education, effectively allowing our students to study what American youth read from the 1820s through the 1950s.

What we have in this current gift is a small but significant window into the Stratemeyer Syndicate, which produced such an outpouring of works from its “fiction factory” from the 1920s through the 1970s, many of which are still in print. Generations of American youth cut their teeth on these stories, myself included–when I was ten I refused to read anything else, my mother had to wean me off these books and branch out, I loved them so much.

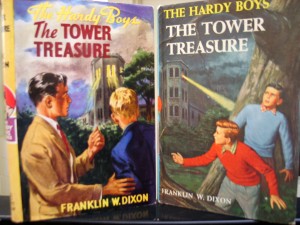

In the 1950’s there were some major revisions done, mostly to update the technology and language (racial slurs were thinned out, etc.)–as one can see from a comparison of the first page of the first Hardy Boys volume, The Tower Treasure, below:

On the left is the 1927 edition, and on the right, the revision done in 1959.

On the left is the 1927 edition, and on the right, the revision done in 1959.

A small exhibition of these books will be mounted in the atrium of the Raether Library and Information Technology Center from January to June, 2015.